Credit: Kratos

LA PLATA, Maryland — Non-geostationary orbit satellite networks are routinely beaming their signals in areas reserved for geostationary satellites, and into each other’s signals as well, according to spectrum-monitoring service provider Kratos.

The interference caused, while real, has up to now not been the source of complaints to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), in part because it is not yet serious enough to be seen as a material issue by the geostationary satellite operators or, in LEO-to-LEO interference, the low-orbit constellation operators.

These operators likely do not understand that the incidents of minor interference to their transmissions is in fact coming from satellite networks trespassing on their radio-frequency territory.

But with more LEO constellations on the way from the United States, Canada, Europe, the situation is likely to get much worse if it’s not addressed.

Credit: Kratos

“If you monitor closely the sky from one point on Earth, you can see it happening every five minutes or so,” said Emmanuel Houdet, Kratos business development manager at Kratos Defense and Security Solutions. “It’s not something unusual, it’s quite common.”

In an Oct. 8 presentation to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Space Sustainability Forum, held in Geneva, Houdet detailed ground-based spectrum monitoring will need to inform decisions to be made at coming ITU meetings, including the next World Radiocommunication Conference in late 2027 (WRC-27).

The threat of LEO constellations’ interference as they pass directly under GEO satellites’ beams has been a subject of debate for 30 years, since the first-generation constellations were proposed. All the broadband constellations of that time went bankrupt or shut down well before full deployment, meaning that rules developed to ensure coexistence were never fully tested.

At WRC-23, LEO constellations win ITU agreement to conduct studies to review whether the rules, called Equivalent Power Flux Density (EPFD) limits, could be loosened given the advances in technology since the original limits were set.

Houdet’s presentation did not address EPFD in detail or express an opinion on whether the evidence from Kratos’s spectrum monitoring network provided any evidence on this point.

The 194-nation ITU maintains 10 spectrum monitoring stations used to settle disputes between members relating to signal interference. Kratos monitoring products are at seven of these sites.

Jorge Ciccorossi. Credit: ITU

Jorge Ciccorossi, head of the ITU’s space strategy and sustainability division, said the organization needed verifiable evidence of spectrum use.

“We have heard about the need to know real parameters of the transmissions. Now we’re going to have the opportunity to see measurements to know the real status of spectrum for space systems in NGSO,” or non-geostationary-orbit, Ciccorossi said in introducing Houdet.

Emmanuel Houdet. Credit: LinkedIn

Kratos has developed a software tool to monitor spectrum from NGSO satellites.

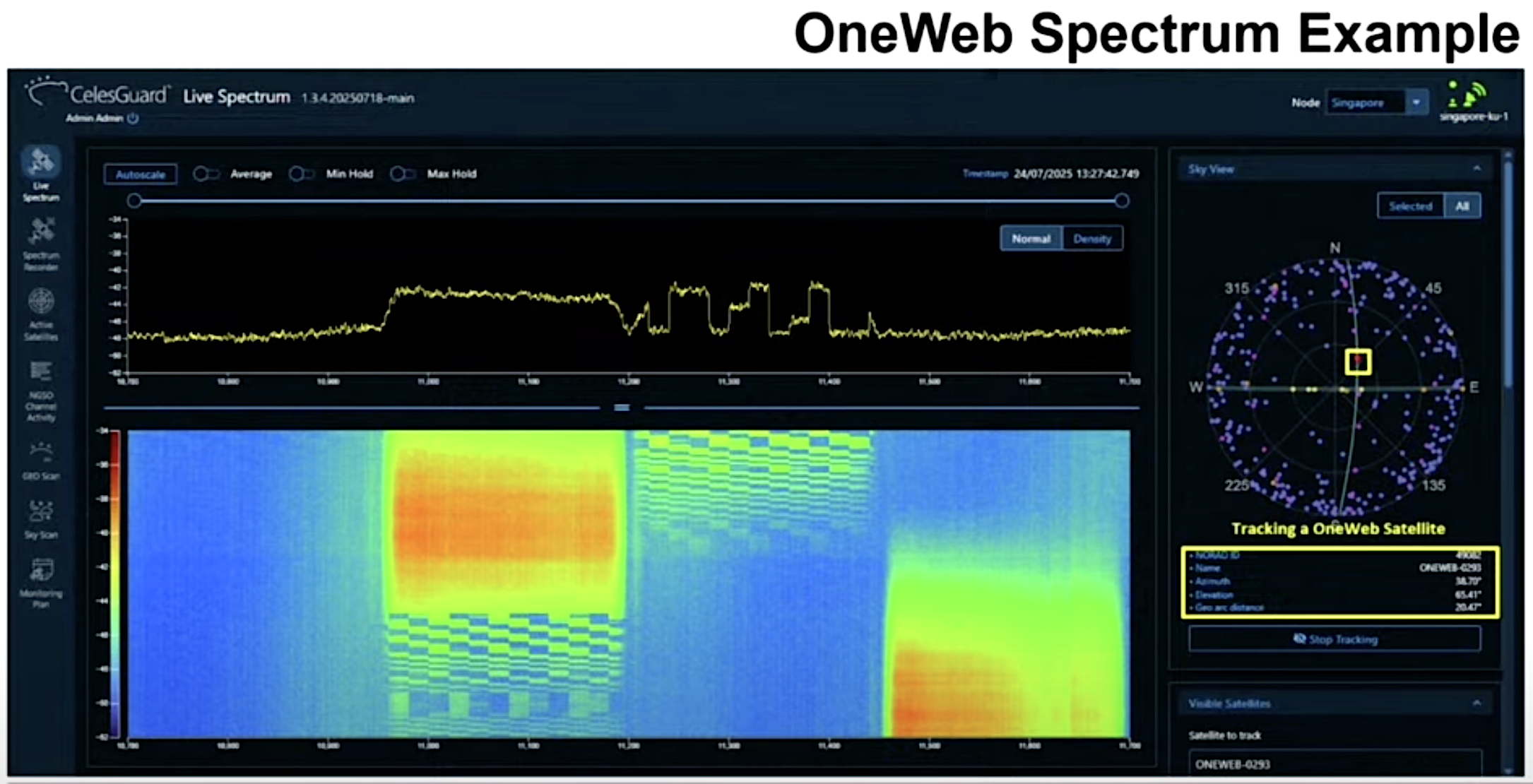

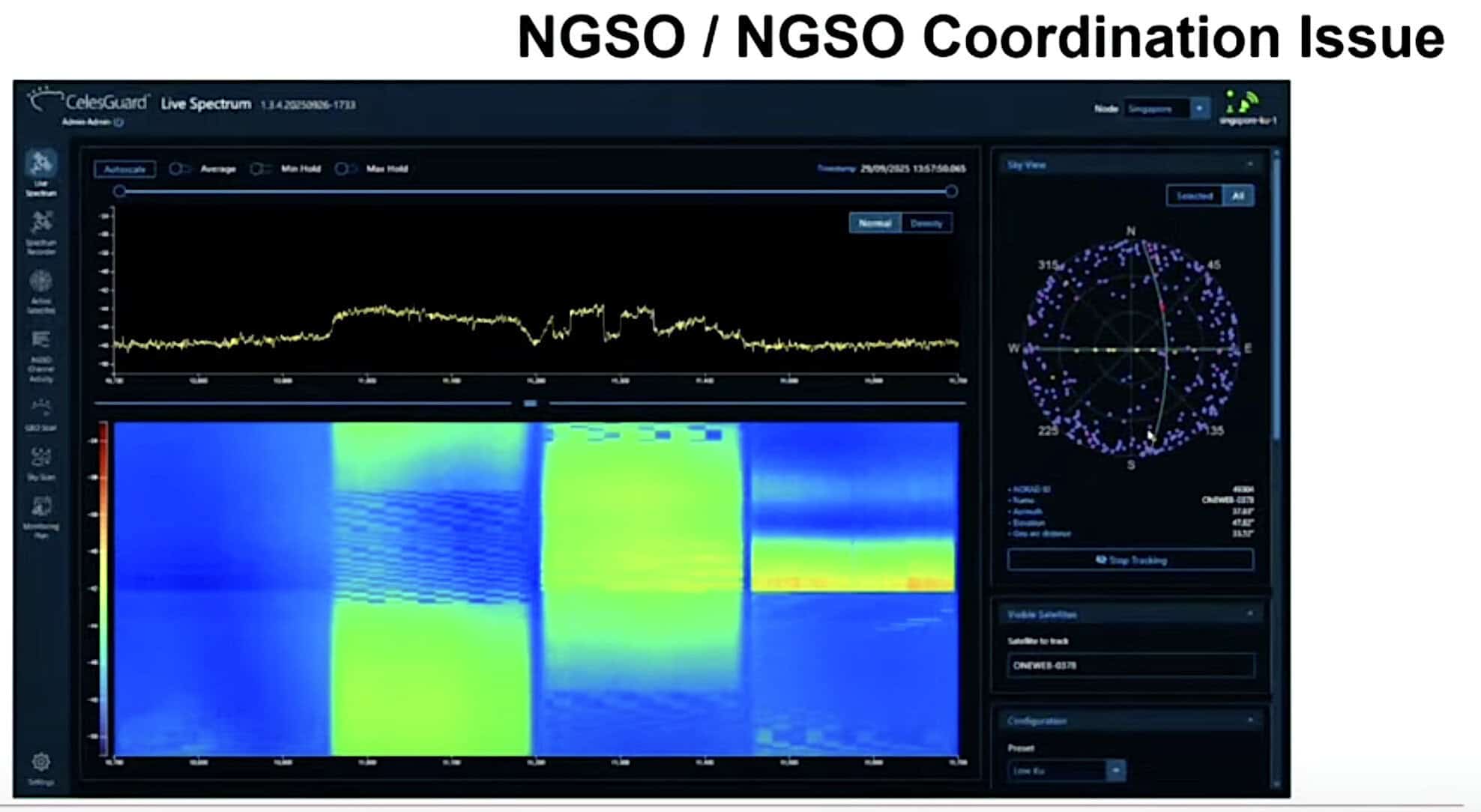

On the right side of the image below is a sky view from the location of the monitoring station. Pink dots are OneWeb satellites, purple are SpaceX Starlink satellites, yellow are GEO satellites and others including SES’s O3b mPower constellation in medium Earth orbit.

Credit: Kratos

A click on the user interface image highlights a given satellite, in this case a OneWeb spacecraft. At the bottom is a waterfall of the spectrum’s recent use history.

OneWeb uses four channels in Ku-low frequency and four in Ku-high. In this image, only Ku-low is being used, with channels 2, 3 and 4 being activated one after another. OneWeb uses only one channel at a time.

Credit: Kratos

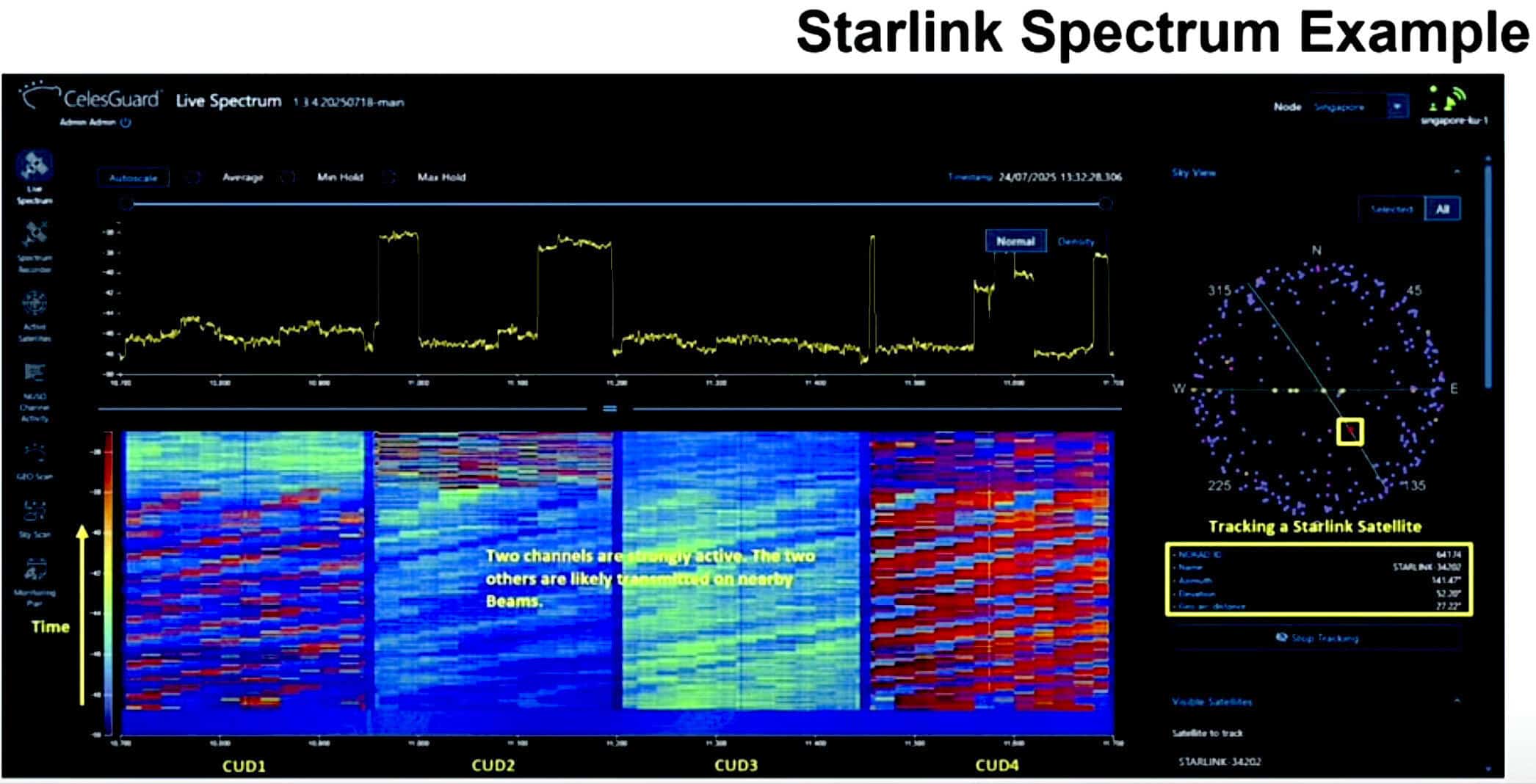

The slide above shows Starlink satellite spectrum use. Starlink is licensed to use the same spectrum as OneWeb but their modulation is not the same and Starlink, unlike OneWeb, can use more than one channel at a time. In this case, the satellites is transmitting from channels 2 and four simultaneously.

Credit: Kratos

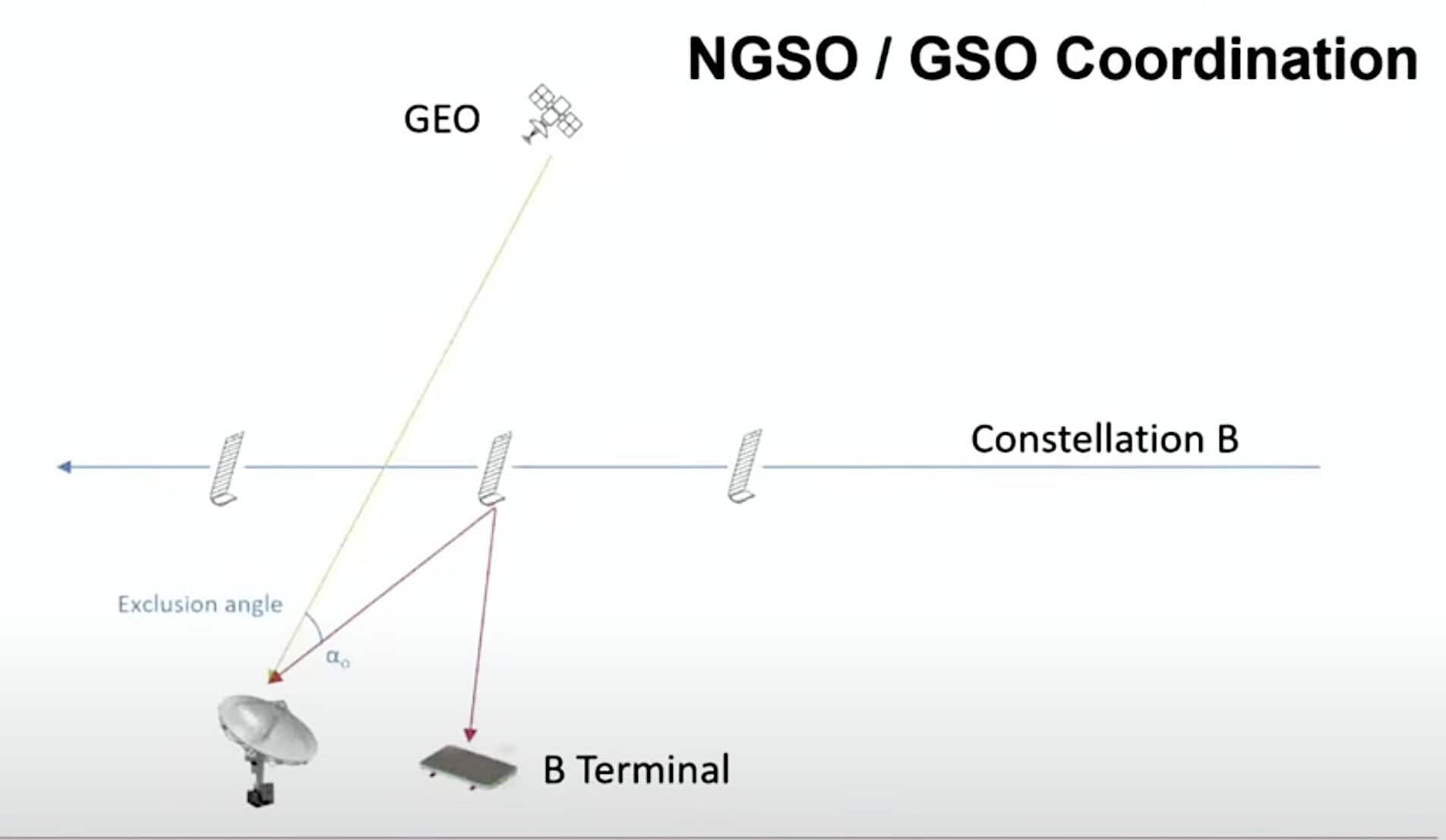

This slide is an illustration showing how NGSO-GEO coordination is supposed to work, based on ITU agreements that were struck, after much debate and resistance from GEO operators, in the 1990s. The rules identify an exclusion zone directly under the GEO arc in which NGSO satellites are not allowed to transmit for fear of interfering with the GEO satellite’s signals.

Credit: Kratos

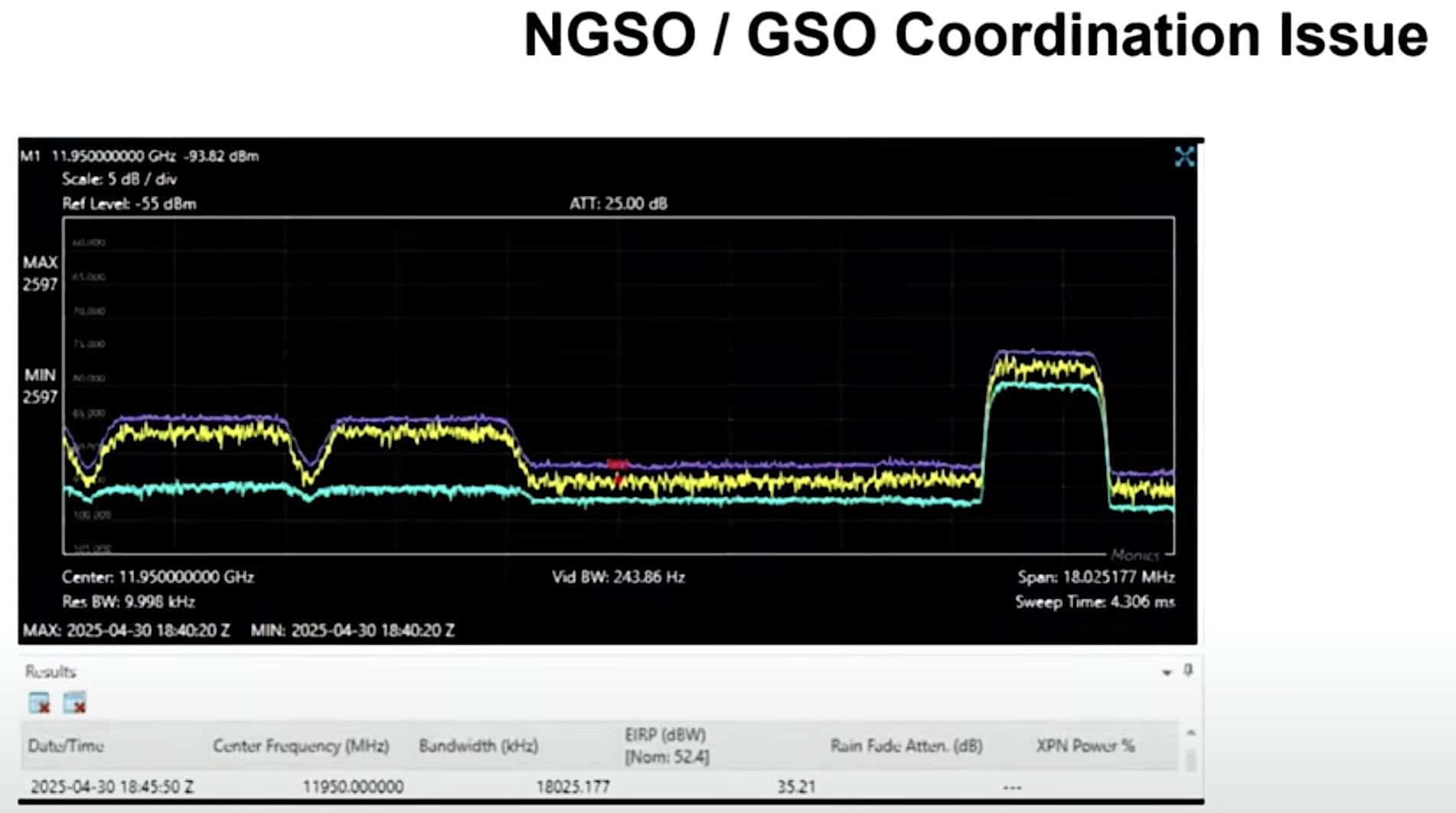

This image shows a live capture of a Starlink satellite nearing the GEO belt a and transmitting on channel 2.

“If we look carefully we can see it has stopped transmitting about 8 degrees from reaching the GEO arc,” Houdet said. “I am not sure this is exactly the right value but still we see it did not interfere with the GEO satellite beams that we see after.

“And now it is going to restart transmitting. Done: Very good. Congratulations to this satellite. It apparently complied” with the regulation.

Credit: Kratos

“But it does not always comply. Based on measurements we have done and have seen, sometimes satellites still transmit a small signal. You can see here the two small signals we see on the real-time spectrum and on the waterfall. This satellite is transmitting while going through the GEO arc.

“It’s not super-powerful, but it still can be disruptive. There are two in this case. Sometimes it’s only one. It’s about 4 MHz of bandwidth.”

Credit: Kratos

The same sequence as seen from monitoring the GEO satellite’s transmissions show a signal coming up. “Based on the power we see, maybe this is disruptive for the GEO satellite services.”

Credit: Kratos

The above image is from monitoring OneWeb satellite 378. The waterfall shows a possible Starlink signal, but it was on Channel 1 while OneWeb was using Channels 2, 3 and 4.

“So far, so good, but then: Wow. A Starlink satellite went through and we have OneWeb and Starlink using the exact same channel at the same time.

“Of course, it’s probably disruptive for both OneWeb and Starlink.”

Credit: Kratos

“If we monitor, there are issues,” Houdet said. “Some GEO and NGSO operators today see issues on their satellites that they don’t necessarily understand. We need to monitor, take measurements, call it data and use this data to qualify what is happening in the sky.

“There will be more constellations. Quianfan [from China] is already flying and doing tests and may become operational. [Amazon’s] Kuiper is launching and will become operational, and there are others.

“In the future there will be more problems. We need to collect data and make sure we have the information for factual discussions and good decisions.”