Carlos Manuel Baigorri. Credit: Anatel

WASHINGTON — The president of Brazil’s telecommunications regulator, Anatel, said current international regulations on registering global satellite communications constellations need to be scrapped to allow for later entry by less-developed countries.

Brazil has been working for several years to win support among International Telecommunication Union (ITU) nations to do away with the “first-come, first served” rules, saying they are a de facto violation of the right of all nations to access orbit.

In a Dec. 9 presentation here at the Americas Space Forum, organized by ForumGlobal, Anatel President Carlos Manuel Baigorri said Brazil will continue to work to persuade the ITU to become more active in space sustainability issues in general — debris mitigation, collision avoidance and signal interference — and specifically in assuring the future access to low Earth orbit by less-developed countries.

It’s an issue that is almost certain to be part of the next ITU World Radiocommunication Conference, WRC-27, to be held in Shanghai.

“These constellations are naturally global operations, unlike GEOs,” Baigorri said. “We have been pushing for rules to give the authority for ITU to deal with this kind of issue. There is a risk of the tragedy of the commons with no rules on how to use it.”

Credit: Anatel June 2025 presentation

Brazil in June hosted the 11th BRICS Communications Ministers meeting, whose final declaration echoed the Brazilian view:

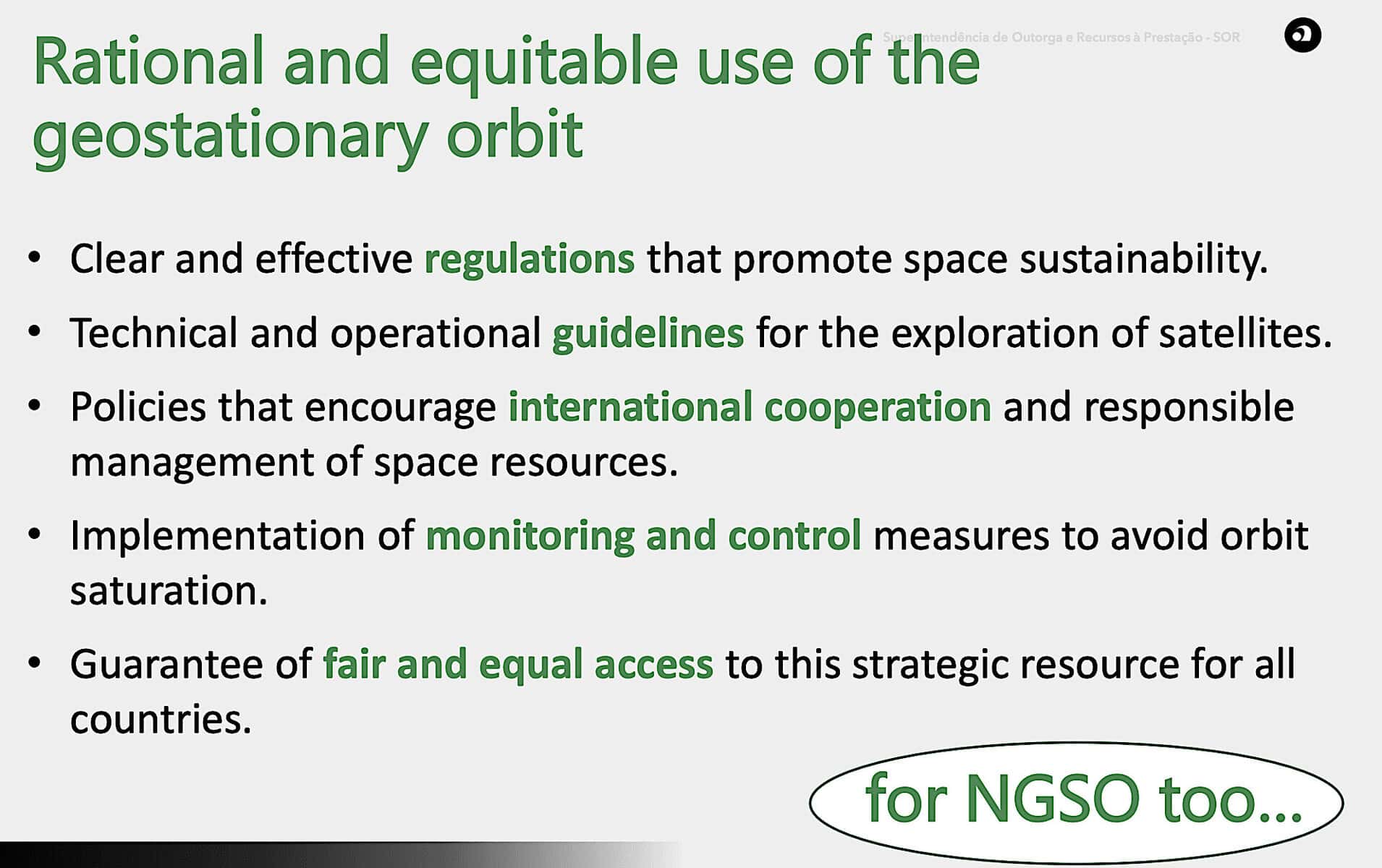

“While we already have generally well-established mechanisms to ensure equal access to Geostationary Satellite Orbit (GSO), the regulatory framework and tools can be improved to ensure equal access to Non-Geostationary Satellite Orbits (NGSO) for satellite systems,” the declaration said. “Reaffirming our commitment to make joint efforts to achieve the rational, efficient, equitable, fair, effective and economical use of spectrum and associated satellite orbits, we encourage further cooperation among BRICS members.”

BRICS began as a five-nation organization of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa but has since expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The declaration also reaffirmed each nation’s right to determine what communications are allowed in its territory, an issue that has resurfaced with global broadband satellite constellations. SpaceX has sparred with India about access to India’s market and Starlink continues to allow its terminals to operate in Iran despite the opposition of the Iranian government.

“We also affirm that the technical reach of space telecommunications systems should not bypass state sovereignty in any case, and the provision of satellite services within the territory of a state should be carried out only if authorized by that state,” the declaration said.

Extending ITU GEO frequency reservations by non space-faring nations to apply to LEO constellations

ITU rules on access to geostationary orbit reserve spectrum for national satellite operators in governments that are years away from using the frequencies.

How this right could be adapted to a LEO or MEO-orbit constellation whose satellites cover the world is unclear and Baigorri did not detail technical solutions that would satisfy less-developed countries’ wish to preserve future access to orbit while permitting global constellations to operate profitably.

Baigorri said the ITU was the best fit for crafting access rules for equitable access and for space sustainability in general.

The Geneva-based ITU has made attempts to extend its authority beyond adjudicating disputes over signal interference and orbital slot reservations to include sustainability but has met resistance.

ITU officials have said the biggest member nations, including the United States, China and Russia, do not want the organization to take on this role.

“Brazil thinks the participation of ITU is crucial in this,” Baigorri said. “We are still waiting to see any effective implementation but we have been pushing for it. There is no kind of equitable access regulation or space sustainability.

“ITU has done that for GEO orbits, guaranteeing that all nations have their fair access. This discussion should happen for LEO and MEO orbits at the technical level at the ITU.”

Baigorri acknowledged that this is not a consensus view at the ITU, whose general policy is to enact rules based on consensus and then allow individual nations to opt out if they choose.

“We are a sector member of ITU and we are aware that this is not a common vision. We have a consensus mechanism and we try to find common ground. In a multilateral framework, each country has one vote and we have to find common ground.

“These are assets of all humankind,” Baigorri said. “You have to understand that different countries are at different moments in their development. You have developing countries and developed countries. It’s not fair for developing and less-developed countries that this asset is only for whoever gets there first to use.

“At the end of the day there are historical moments for each one of these countries. It’s not because one specific country has the ability to use it right now that it can go there and grab everything so that when other countries are ready to use it it is over exploited. That’s the question: How do you create conditions to share a common good that is for all the countries? There is no owner of the orbits. This is the point we are bringing up and what we are bringing up for discussion at the ITU.”