Darren McKnight. Credit: Secure World Foundation

SYDNEY — The mass of derelict rocket upper stages being left in low Earth orbit each year exceeds the amount left 20-plus years ago, often clustered in the same region, despite decades of non-binding rules urging that they be brought down to avoid debris-creating collisions, according to Darren McKnight, senior technical fellow at space surveillance company LeoLabs.

McKnight, who has a long history assessing orbital-debris issues, said the practice of leaving rocket upper stages in orbit after they deposit their satellites, coupled with the increased number of large low-orbit constellations being deployed, is raising the risk of a major debris-creating event.

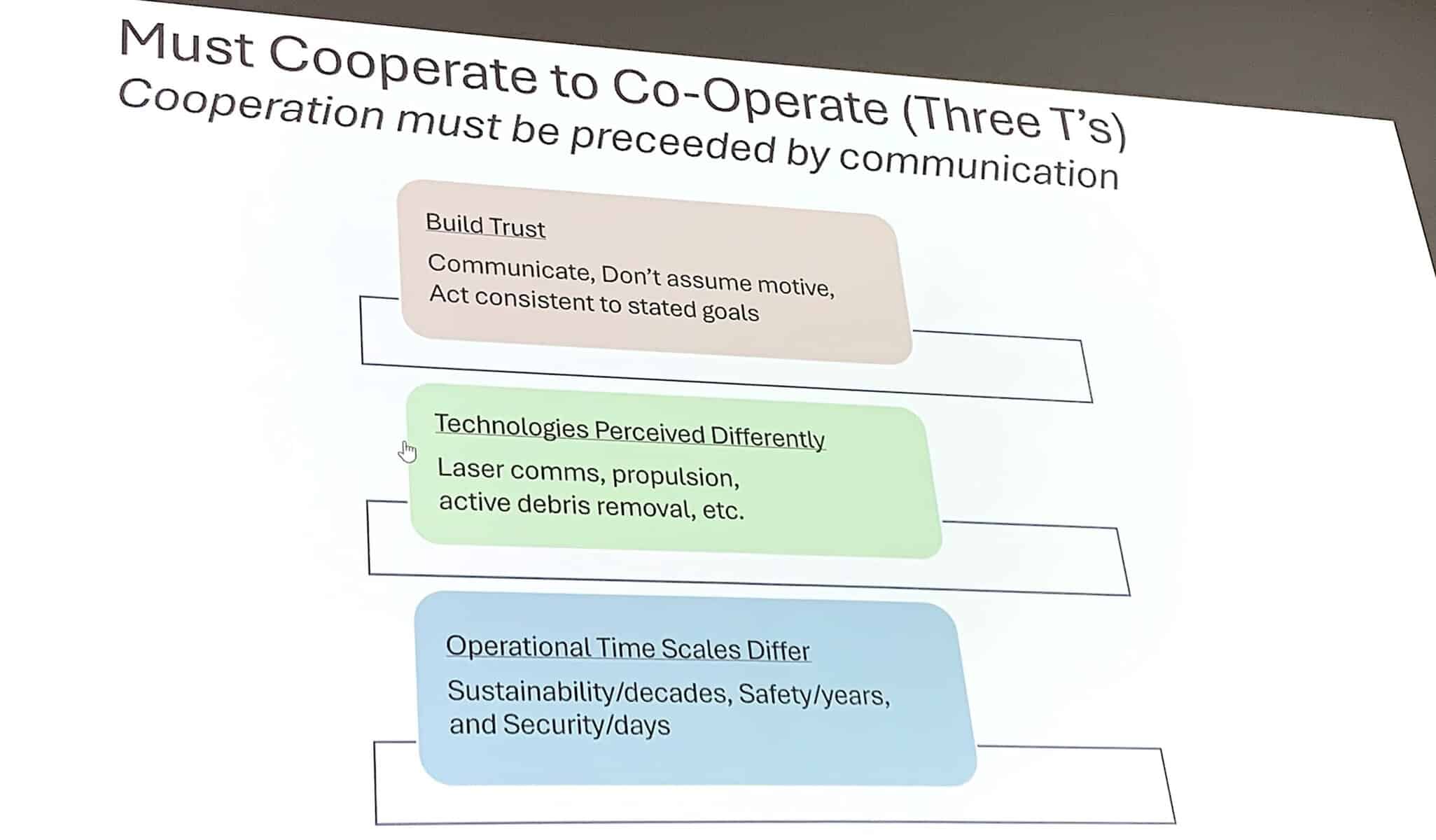

In a Sept. 29 address here at the 76th International Astronautical Congress (IAC), McKnight said the rapid deployment of constellations, especially by the United States and China, is becoming dangerous not so much because of the raw numbers of satellites, but because Chinese and US operators are not communicating on their maneuvers.

“Unfortunately, there are some trends that still haven’t stopped,” McKnight said. “We are still abandoning, as a space community, more rocket body mass in a year than we did before the turn of the century. Even though we have the 25-year rule, even though we know how bad it is, we are still leaving them at a higher rate than before.

“Clearly there is a communication disconnect. And the dead objects now on average have a greater mass. On average now these objects we’re leaving are like 1,300 kg compared too 800 kg.

“This is all in the wrong direction. We’re doing something wrong.”

The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), after long accepting the industry-standard advisory that objects should be removed from orbit, or put into orbital graveyard, within 25 years of retirement, has tightened the rule to five years.

“People said 25 years isn’t good,” McKnight said. “Five years isn’t good enough either by the way. Whey don’t we have a one-year rule? If you’re finished with space hardware, bring it down, because it’s going to affect space sustainability.”

Some regulators have countered that if multiple operators are ignoring the 25-year rule, they are not going to abide by by a five-year rule either, unless — and this is what the FCC is doing — violators suffer penalties.

The growth of large constellations of broadband satellites is a more complicated issue, and potentially more urgent. The constellations’ operators need to communicate with each other on their planned maneuvers to prevent collisions. In many cases they are not doing that. A major reason is current US-China relations.

“We are at the point where the growth of constellations is going to be exponential,” McKnight said. “If we don’t manage it well, through space traffic coordination, we are going to have problems.”

For now, it’s SpaceX Starlink and, coming soon, Amazon’s Project Kuiper; and Europe-based Eutelsat’s OneWeb constellations. China has two broadband constellations, Guowang and Thousand Sails, each planning more than 10,000 satellites. Both have begun launching their networks.

Cooling China-US relations has made it more difficult to talk openly about space safety issues than it once was, even though such communication is needed now more than ever.

“It’s a bare minimum for constellations near each other to be working together, to show your work. How are you determining your collision risk to others? How are you determining the probability of collision — with what algorithms, what uncertainty?

“What pC [collision-risk probability] threshold are you going to use to determine to make a risk-reduction maneuver? You’ve got to talk at that level or else we are not going to be able to work together in space.”

McKnight said all constellation operators should, as Starlink does, publicly release their satellites’ ephemerides, providing location and trajectory and allowing other operators to make adjustments if needed.

He said Starlink and OneWeb collaborated closely when OneWeb began launching and was raising its satellites, after separation from the rocket, to higher orbit, passing through Starlink operating orbits.

“OneWeb should be applauded for the amount of work they put in to show how am they were going to safely go up there. They showed their work. They shared their work.”

It’s not rocket science, but social science that’s lacking

This kind of communication, and more, has been made necessary by the arrival in low Earth orbit of the Guowang and Thousand Sails constellations.

SpaceX and OneWeb have both been LeoLabs customer, but McKnight said he was assessing the situation neutrally. He acknowledged that US policy prohibiting communications with China by NASA and a few other US agencies is not helpful.

The policy comes from the 14-year-old Wolf amendment that remains on the books. The amendment refers only to direct, bilateral talks, meaning NASA and the White House could engage in discussions with China as part of a multilateral effort.

McKnight said his communications with Chinese officials suggests they may view the Wolf amendment as more extensive than it actually is.

In any event, the current status of communications with China is far from what’s needed under the current circumstances in low Earth orbit.

“[A] maneuverable, non-cooperative spacecraft is actually worse than a piece of debris,” McKnight said. “It’s much more reliable than a satellite that can move and you don’t know why and you don’t know when. So space traffic coordination is really going to matter when it comes to constellations.”

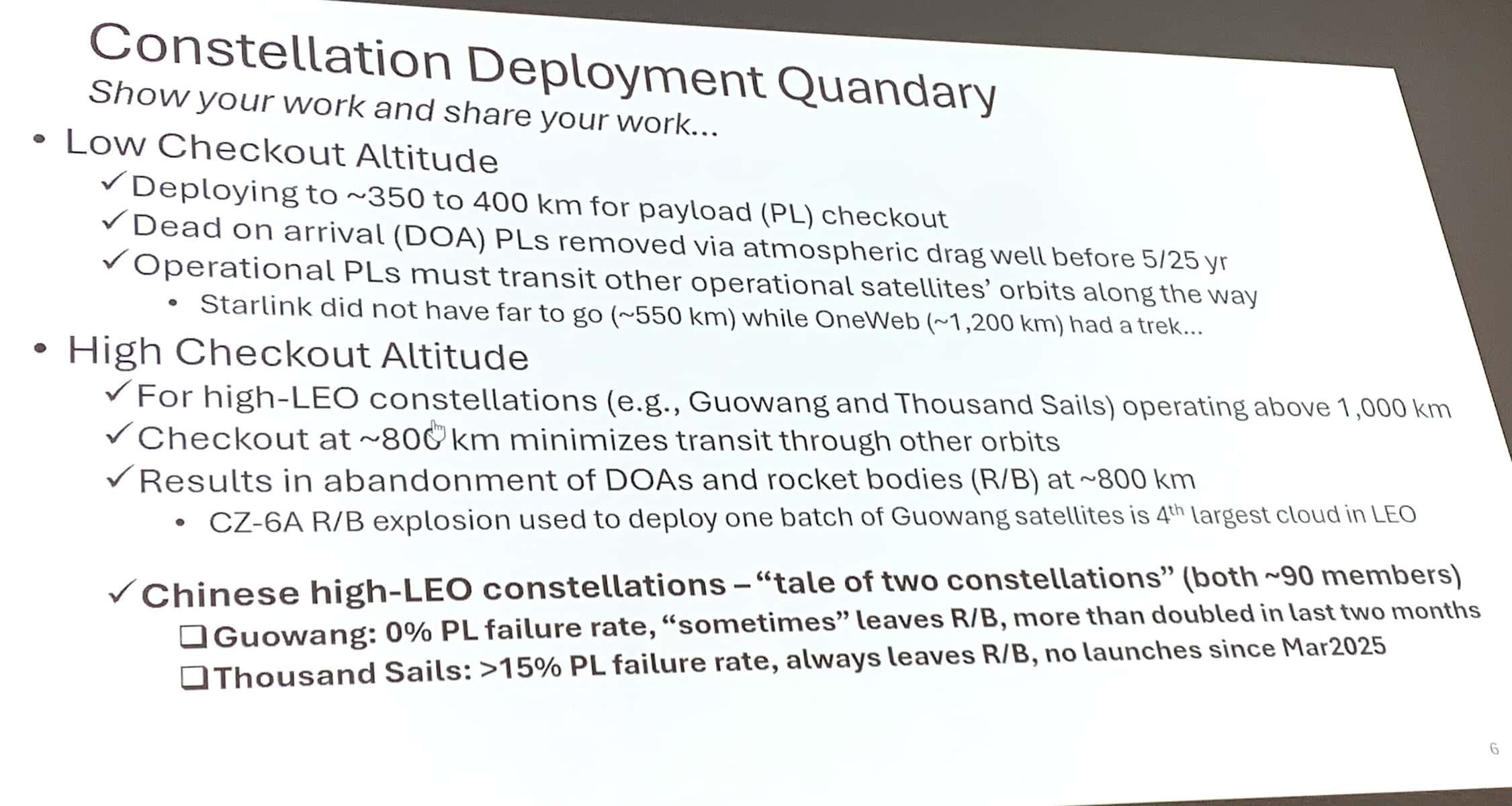

Launching satellites into low orbits before raising them to their operating positions allows operators to validate their performance. Defective satellites can then be left in the lower orbit and to reenter the atmosphere more quickly.

McKnight said Guowang and Thousand sales are being dropped off at 800 km, then moved to their operating positions above 1,000 km.

“That’s great, because they are not transiting from 300 to 800 km. It’s reducing the space safety issues,” he said. “However, they also leave rocket bodies there. The payloads are being deployed by an upper stage. If the stages are dead on arrival and those satellites die, it’s at 800 km rather than 400 km.”

The 5,800-kg upper stage of a Chinese Long March 6A rocket has exploded repeatedly at around 800 km, including during the 2024 launch of a group of Thousand Sails satellites. “It is now the fourth-most-prolific cloud in low Earth orbit,” McKnight said.

He contrasted this the performance of the Guowang network.

“Guowang is amazing: Zero failures. When they use a Long March 5, they can deploy 10 satellites — and no rocket body. How do they do that? They should be talking this up as a wonderful thing. It’s a wonderful opportunity to say, We are being more sustainable. That’s a great story. It’s not being heard about.”

The Yuanzheng upper stage used with the Long March 5B rocket is restartable.

Thousand Sails, on the other hand… “More than a 50% failure rate. Other constellations, when they first got deployed, had failure rates close that. But this is at 800 km and they leave the rocket body.

“These are a lot of facts here, with very little communication about what’s going to come next,” he said.

“How do we cooperate and collaborate with these folks? This is a real quandary: I am not picking sides. I understand there is benefit to both directions. But we are at a point where we’re talking about 1,000 satellites that are going to be deployed at these high altitudes.

“Within three or four years, we’ll have constellations from different countries operating at the near-same altitude, and we are not yet showing and sharing our work.”

McKnight said OneWeb and Starlink were both contacted by a Chinese constellation operator to talk about future maneuvers. “So there is some progress,” he said.

But there needs to be a much fuller two-way flow of information with so many satellites operating so closely together.

“In the next five years, if we don’t deal with the social sciences as well as we’ve done with the physical sciences, we are going to have a problem in low Earth orbit with these constellations,” he said.