Credit: UNOOSA/EU DG-Defis presentation to UN General Assembly

LA PLATA, Maryland — US and European Union government officials agreed they will need to coordinate their space traffic management systems to assure data consistency for satellite operators using the services for collision avoidance.

Both the US Office of Space Commerce (OSC) and the EU Commission Defense and Space Directorate (DG-Defis) are moving ahead with space traffic coordination initiatives despite facing uncertainties about these efforts’ future.

OSC’s Traffic Coordination System for Space (TraCSS) is not certain to survive final budget arbitration in the US Congress, although it has dodged an initial threat to dent it funds following a remarkable appeal by seven space industry associations representing 450 companies: bit.ly/4h7uQTJ

The proposed EU Space Act, which gives the European Commission regulatory powers over satellite fleet management and launch services with the goal of promoting space safety, faces at least a year’s discussion among the 27 EU nations and the EU Parliament.

Challenges to the EU Space Act are expected on legal grounds — whether the Commission has the authority to impose this kind of regulation on the space sector — and on whether the specific policy recommendations strike the correct balance between mitigating debris and collision risk and imposing constraints on industry.

OSC and EU Commission officials attending the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Space Sustainability Forum Oct. 7-8 in Geneva did not address their specific challenges but acknowledged that, whatever else happens, cross-border coordination is key.

Muriel Borowitz. Credit: OSC

“TraCSS is currently in operation with 24 pilot users with around 8,000 satellites,” said Mariel Borowitz, head of space situational awareness engagement at OCS. One of those users is SpaceX’s Starlink, which alone operates 8,500 satellites in low Earth orbit.

TraCSS provides operators’ information on potential collisions based on orbital surveys taken six times a day. Users upload their satellites’ planned movements to the TraCSS website and receive advisories on potential close approaches “within minutes,” Borowitz said.

TraCSS is scheduled to be released in January “and all operators will be able to get space safety information free of charge,” Borowitz said. “Operators want more information-sharing and ephemerides and TraCSS now supports that, allowing for an open and transparent approach to information. We will make that information publicly available. You won’t even need to register to get access to that.”

TraCSS is designed to take over responsibility for commercial space traffic monitoring from the US Defense Department, which over decades has built the Space Surveillance Network of ground- and space-based sensors that is generally considered without equal.

But Borowitz said OCS recognizes that different space-monitoring systems may not produce identical information and that satellite fleet operators need as much certainty as possible before conducting a collision-avoidance maneuver.

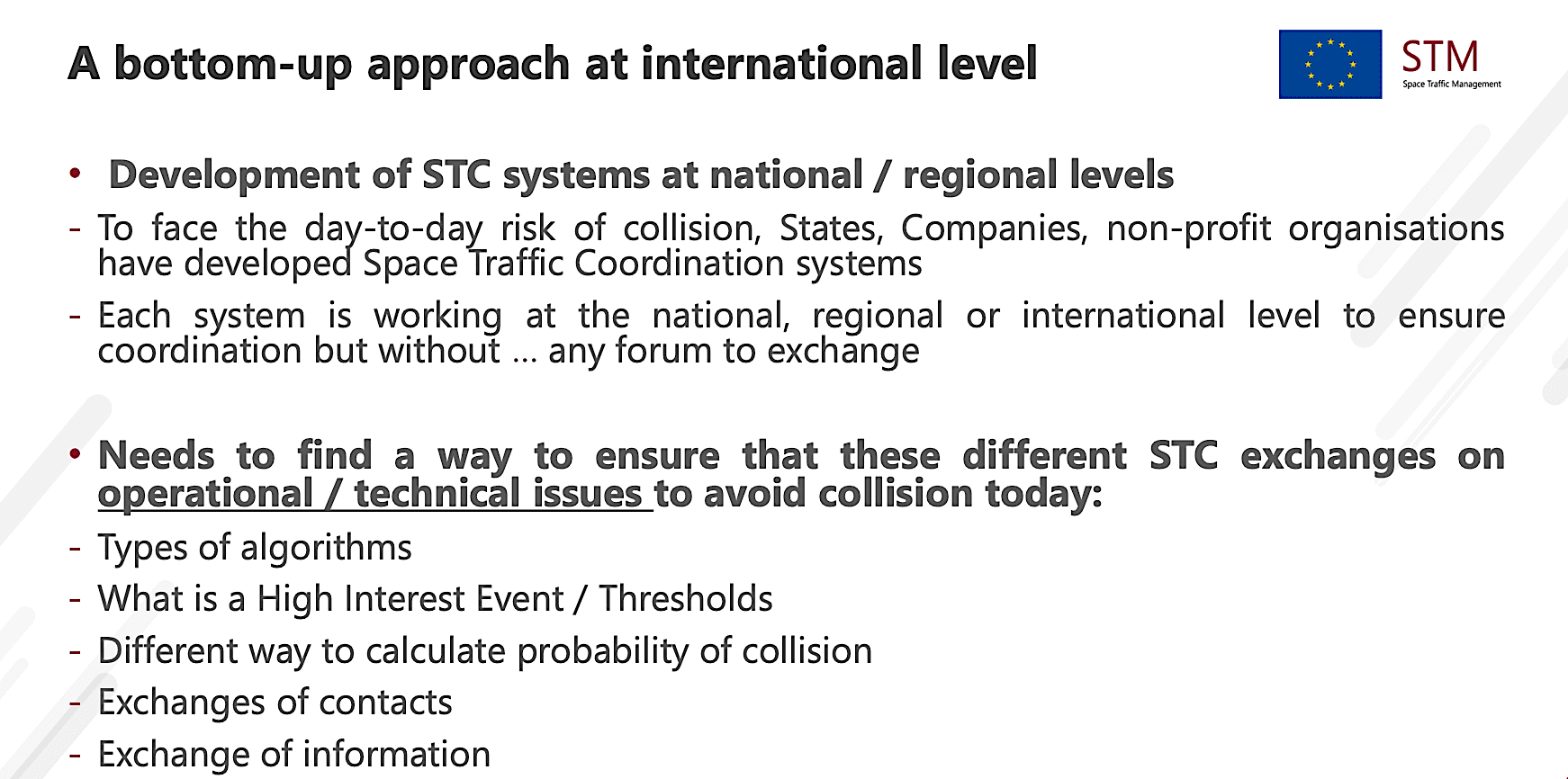

That requires cooperation with other space situational awareness (SSA) systems outside the United States. OSC has already begun talks with the EU Space Surveillance and Tracking (EU SST) service on coordination, and with the European Commission on possible modifications to the EU Space Act.

“We recognized from the beginning that [TraCSS] is one of many SSA systems in the world,” Borowitz said. “If you are going to use it for decision making, you need to provide consistent information, information they [users] can understand.”

The draft EU Space Act, published in June, is a complex document that has already drawn fire from multiple quarters.

Rodolphe Muñez. Credit: ITU video

Rodolphe Muñoz, a legal officer at DG-Defis, made the basic case for the Space Act to the ITU audience.

“We all know the figures,” Muñoz said. “We have huge and growing number of satellites, and it’s very good and will not stop — 13,000 and growing, 140 million pieces of debris and growing, and 1.3 million ITU filings [for future satellite networks]. Not all will materialize, but still we have this equation and if you add the figures you have a catastrophic event. What to do?”

Muñoz praised the UN’s 21 Long-Term Sustainability Guidelines for space conduct — “a wonderful tool, but nonbinding. Isn’t it time for member states to implement these guidelines. Industry needs to convince member states that they need to develop this. Otherwise, their industry will be destroyed. This is what we are trying to do with the Space Act.”

Coordination with TraCSS and other SSA systems is essential. “Today we have no coordination working and this has to be developed. We need to work together to avoid something that we all fear but sometimes forget: That we might lose everything” if low Earth orbit is rendered all but unusable following debris-creating collisions.

The Commission has joined with the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) to train governments to develop their own SSA systems.

The EU Space Act, if adopted, will have the effect of regulation starting in 2030.

“Why have something binding? Saying you need to put on your seatbelt, not phone or watch [a screen] and need a driver’s license — without these compulsory rules, do you think they would be applied?

“EUSPA [the European Union Agency for the Space Program] now has to run after EU operators to get them to register” their networks,” Muñoz said. “It’s free of charge, there are no tricks where we send a bill. The idea is, we need binding rules now, before it’s too late.”

He encouraged government and private-sector representatives to send comments to the DG-Defis website on the EU Space Act.

“The fact is we were the first out of the woods with the Space Act,” Muñoz said. “If you have comments, we will read them. Approach us and we will engage. We are modest and ready to learn if, according to you, something should be better drafted.”